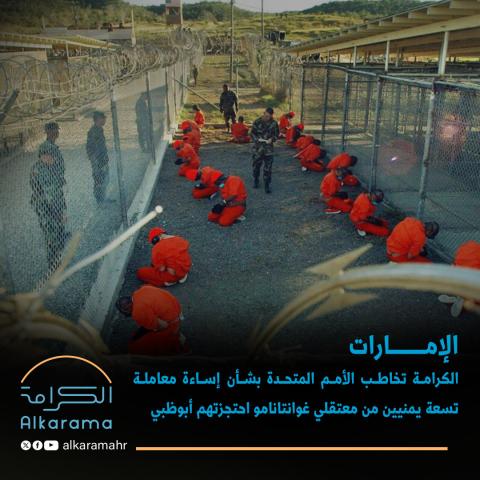

On 24 December 2025, Alkarama submitted a complaint to the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD) regarding nine Yemeni nationals who were formerly detained in Guantánamo Bay. Having been deprived of their liberty by the United States for several years without charge or trial, they were transferred to the United Arab Emirates between 2015 and 2016 on the understanding that they would be released upon arrival. However, upon arrival, they were mistreated and taken to a secret detention facility.

More than twenty years after Guantánamo opened in January 2002, this case illustrates the enduring effects of the camp's exceptional detention regime, the consequences of which continue to be felt far beyond its barbed wire fences. The victims' transfer did not mark the end of their suffering, as they were sent to a country where serious and systematic human rights violations are well-documented.

The nine men were arrested by Pakistani security forces in the context of operations carried out following the 11 September 2001 attacks and handed over to US authorities without any judicial process. They were subsequently transferred to various detention centres under US military control before being sent to Guantánamo.

Testimonies collected by Alkarama establish that the victims were subjected to particularly severe treatment from the moment they arrived in the United Arab Emirates until their release. This treatment included prolonged solitary confinement, physical violence, torture, degrading sanitary conditions and a lack of adequate medical care.

These detentions took place outside of any effective judicial framework, thereby prolonging the state of legal uncertainty that had already characterised their situation in Guantánamo. For these men, therefore, this was not a release, but merely a transfer of detention to another territory. Between 2021 and 2022, Emirati authorities forcibly repatriated these men to Yemen, to areas controlled by armed militias financed by the United Arab Emirates.

These transfers were carried out without their consent or an individual risk assessment despite the country being engulfed in an armed conflict marked by serious human rights violations. According to the submission addressed to the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD), these returns violate the principle of non-refoulement, which prohibits transferring a person to a country where they face a real risk of torture or inhuman or degrading treatment.

In this case, it is clear that both the United States and the United Arab Emirates are responsible for the harm suffered by the victims. Washington is accused of organising the transfers without sufficient procedural safeguards, despite being aware of the risks involved. The Emirati authorities, for their part, are implicated in secret detentions, ill-treatment and forced repatriations.

This case highlights the systemic nature of violations associated with Guantánamo. Even after they are formally released from the US facility, the consequences persist in the form of restrictions on movement, social stigmatisation, an inability to reintegrate and an absence of any form of reparation.

Today, the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention is the only international body capable of determining the illegality of these deprivations of liberty and of providing moral and symbolic reparations to the victims.

Over two decades since the first transfers to Guantánamo, this referral highlights that accountability and justice for former detainees remain largely unresolved.