In 2016, we submitted to the UN Mechanisms 3 communications regarding 2 individuals.

OMAN

Our Concerns

Our Concerns

- Restrictions on the rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly;

- Systematic practice of arbitrary detention of human rights defenders and political activists or dissidents;

- Reprisals against peaceful activists and journalists.

Recommendations

Recommendations

- Ratify all core international human rights instruments;

- Ensure detention conditions comply with the UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners and apply all fair trial guarantees;

- Guarantee the free exercise of the rights to the freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly;

- Fight impunity by prosecuting any perpetrator of grave human rights violations at all levels.

Upcoming

Upcoming

Despite being a founding member of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), Oman is the only Member State not to have partaken in the efforts to restore the rule of the Hadi government in Yemen. In fact, as a result of its neutral position in the Yemeni conflict, the UN Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen consulted Oman in November to find a solution to the crisis. Indeed, earlier during the year, the Sultanate also negotiated the release of a US citizen from Yemen. In June 2016, following the outcome of Brexit, rumours emerged that Oman was similarly considering to opt out of the GCC. Omani officials denied these rumours, however, insisting that they intended to remain part of the Council.

2016 was also marked by a number of strikes by foreign workers over the withholding of salaries by their employers and their being housed in unhygienic facilities. Domestic foreign workers have emerged as a particularly vulnerable group within the GCC in general, including in Oman. Hence, in February 2016, Indonesia temporarily banned domestic workers from taking up employment in Oman. In April, the Omani Ministry of Manpower announced plans to increase the legal protection offered to those falling within this particular category of workers, who had thus far been excluded from labour laws entirely.

The beginning of 2016 saw the transfer of ten Yemeni Guantanamo detainees to Oman, a transfer described by the authorities as a “temporary stay” for humanitarian reasons, as these individuals were unable to return to their home country, ravaged by war. Although the move was presented as a positive development towards the shutting down of Guantanamo, no details were publicised about the conditions of their release, for instance, whether or not they would be detained in Oman. If so, this would constitute a violation of their basic human rights.

On the legislative level, the Omani Council – the country’s bicameral Parliament – has, since April, been studying amendments to the Penal Code. These amendments seek to add a section on defamation, which could prove harmful to the freedom of expression, a right that was seriously limited during 2016. Indeed, besides the prosecution of journalists, some publications resorted to self-censorship and shut down in light of the “circumstances” in the country. Both Mowaten magazine and Al Balad newspaper bid farewell to their readers this year.

Lastly, the end of 2016 saw the return of Omanis to the polls for local elections. Omanis were allowed to elect their local representatives for the first time in 2012, spanning a four-year term. However, the latter only have limited powers, since the Chairmen and Deputy Chairmen heading the 11 municipalities are not democratically elected, but are instead appointed by the authorities. On 26 December 2016, results demonstrated that out of the 202 councillor seats, only seven will be filled by women.

Repeated arrests and persecution of human rights defenders

In Oman, human rights activists and peaceful dissidents are systematically targeted for their dissenting opinions and criticism towards governmental policies. Human rights defenders are arrested, interrogated, and then released, only to subsequently be re-arrested and eventually tried on the basis of laws restrictive to their basic freedoms. Their deprivation of liberty is often arbitrary and they are usually victims of a number of other violations during their detention, including, for example, the extraction of confessions under duress, which are later used as evidence during unfair trials.

For instance, Said Jadad, a blogger and prominent human rights defender who has previously documented human rights violations in his country, led a series of protests in the Dhofar province, southern Oman, peacefully called for reforms in the country. He has been arrested several times and was held without charges in December 2014, following a meeting with the UN Special Rapporteur on the Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and Association, Maina Kiai. He was arrested again in 2015 and held in solitary confinement for the entire period of his interrogation. On the basis of confessions made during previous interrogations, which focused on his activism and ties to international organisations, Mr Jadad was subsequently charged and sentenced by the Court of Muscat for “inciting demonstrations”, “disturbing public order”, and “undermining the prestige of the Court”. The execution of his three-year sentence was however suspended by the Court of Appeal. Mr Jadad was also sentenced by the Court of Salalah to one year in prison and was released in August 2016, after serving a sentence for “using information technology to prejudice public order” for having compared the 2014 Hong Kong protests to those of Dhofar in 2011 in a social media post.

In May 2016, Talib Al Mamari, an Omani parliamentarian and a vocal proponent of the rule of law and the protection of the environment, who received the Alkarama Award for Human Rights Defenders in 2015, was released by royal pardon. He had been arrested in August 2013 for having taken part in a demonstration against pollution in his home town of Liwa. In October 2013, he was interrogated and released on bail, only to be re-arrested later that same day. He was then held in solitary confinement until the end of his trial in December of that year, when he was sentenced to four years in prison for “harming the State’s prestige”, as well as to one additional year for “disturbing public order” and “obstructing traffic”. Retried a number of times, his sentence was confirmed on appeal in October 2014. A month later, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention recognised his detention as arbitrary and called for his immediate release. For over 18 months, the Omani authorities refused to implement the WGAD’s decision.

These series of reprisals must be understood in the context of a culture silencing civil society, which is implemented through a systematic use of arbitrary arrests, incommunicado and secret detentions, as well as unfair trials against all dissident voices, regardless of their peaceful nature..

Still no ratification of the core human rights instruments

To this date, Oman has only ratified four of the nine core international human rights instruments. It is the only Arab country that is not a party to any of the conventions protecting fundamental rights, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the Convention against Torture (UNCAT) and the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (ICPPED). These UN treaties provide greater protection to the rights and freedoms afforded in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

During its Universal Periodic Review in November 2015, Oman received 232 recommendations from UN Member States, 53 of which called for the ratification of the outstanding core human rights conventions, notably the ICCPR and the UNCAT. At the time of its review, the Omani delegation confirmed that “the Sultanate had agreed in principle to adhere to the following conventions: the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; and the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance”. However, more than a year after this statement was made, Oman has yet to fulfil its promise. Furthermore, the delegation did not refer to Oman’s possible intention of ratifying the ICCPR, which protects fundamental rights and freedoms, such as the freedom of opinion and expression and the freedom of peaceful assembly and association; freedoms that, in practice, the Sultanate severely infringes upon. If Oman wishes to strengthen its commitment to human rights and provide its citizens with serious guarantees, it must ratify these conventions.

RESTRICTIONS TO FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION, SPECIFICALLY TARGETING JOURNALISTS

2016 saw numerous arrests and prosecutions undermining the freedom of expression and targeting artists, journalists, and writers. Indeed, in February, a renowned caricaturist was sentenced to three months in prison for the contents of a Facebook post. During the same month, former diplomat Hassan Al Basham was sentenced to three years in prison for posts he published on social media, convicted of “lese-majeste crimes and of blasphemy”. In April, writer Abdullah Habib was arrested for calling on the Sultan to reveal where the individuals killed during the Dhofar rebellion of 1970 had been buried. Other individuals including writers such as Saud Al Zadjali and Hamood Al Shukaily were arrested later during the year for similarly expressing their opinions.

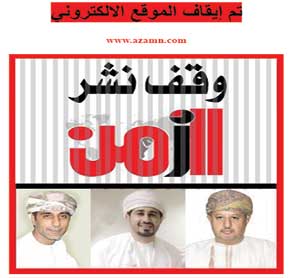

This government crackdown on the freedom of expression in Oman was even more starkly illustrated by the shutdown of Al Zaman newspaper and the arrest of three of its journalists following the publication of a series of articles exposing corruption and questioning the independence of the judiciary.

In late July and early August 2016, a few days after the publication of an article uncovering corruption of the judiciary entitled “Supreme bodies tie the hands of justice”, Al Zaman’s editor-in-chief, Ibrahim Al Ma’amari, was arrested, as well as his colleague Zaher Al Abri. On 9 August 2016, after a follow-up article had been published on the issue, the Ministry of Information ordered the newspaper’s closure and another of its writers, Yousuf Al Haj, was arrested by Internal Security officers and detained incommunicado for two days. Denied the right to meet with his lawyer before his first hearing on 15 August 2016, he was charged, inter alia, with “undermining the status and the prestige of the State”, “publishing what might be prejudicial to public security”, and “contempt for the judiciary”.

On 26 September, the Court of Muscat ordered the shutdown of Al Zaman newspaper. It sentenced Yousuf Al Haj and Ibrahim Al Ma’amari to three years in prison and Zaher Al Abri was sentenced to one year in prison, respectively. Yousuf Al Haj has since been released on bail and is now awaiting the verdict of the Court of Appeal. He reported that during his detention, he was held in solitary confinement, resulting in the deterioration of his health.

While this restriction of the freedom of expression is a pressing issue in Oman, it is not new to the Sultanate. Indeed, after his visit to the country in 2014, the Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association had already expressed his concern about “a pervasive culture of silence and fear affecting anyone who wants to speak and work for reforms in Oman”.